The concept for “Whether Ewe Like It or Not” derives from the European myth of the “vegetable lamb.” Cotton, woolly yet breathable, like linen, was so exotic to Europe that people couldn’t conceptualize it. They invented a complex artificial reality in which cotton grew, like wool, on sheep that grew on trees.

Beginning in the Renaissance, scholars studied, looked for, and found “scientific” evidence of “sheep trees.” The theory wasn’t debunked until the late 1800s with the publication of the Vegetable Lamb of Tartary. The works in the show are derived from historical drawings of these pseudo-plants.

Today, I see propaganda that reminds me of “sheep trees” everywhere. My public school American History classes, for instance, presented a number of “sheep trees” that obscured our country’s troubled past: I didn’t learn how the hunger for cotton and its revenues led to slavery or the genocide of Native Americans. I didn’t learn about the Triangle Trade in which the Northern US / Union States and Europe were complicit. I didn’t learn that our country’s wealthy wouldn’t have anywhere near the wealth they have if it weren’t for the countrywide production of cotton. Instead, I learned about “sheep trees”: the noble rebellion of the colonies against British rule, how the civil war was a “states’ rights” issue, and how slavery ended (but not how the Thirteenth Amendment allows forced labor to thrive to this day). Believing in these “sheep trees” has had a profound effect on my success as a voter and taxpaying citizen. Swayed by competing narratives, I am complicit, yet also a victim of a powerful propaganda machine designed to control flocks of Americans. Double bummer, and I know ewe can relate.

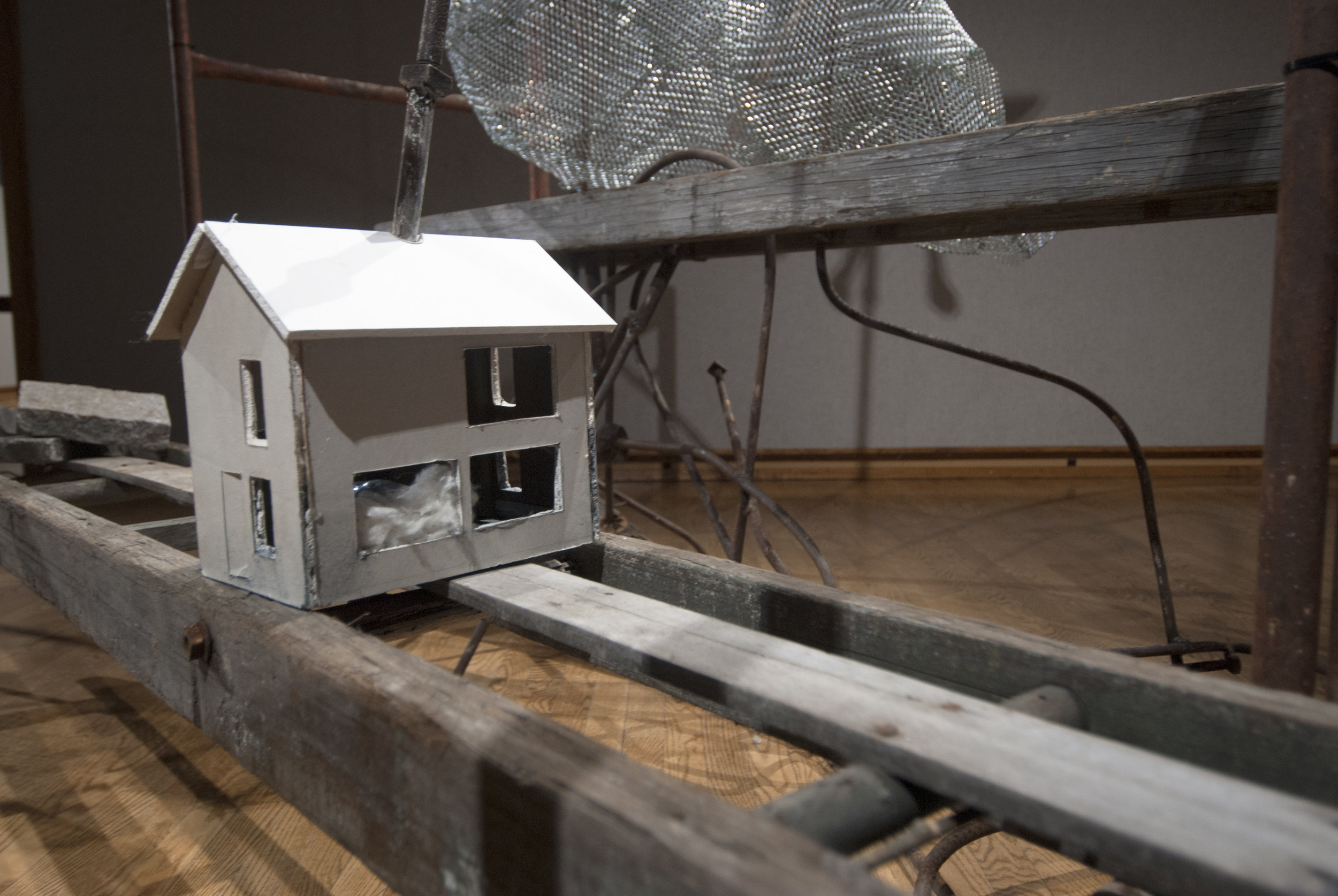

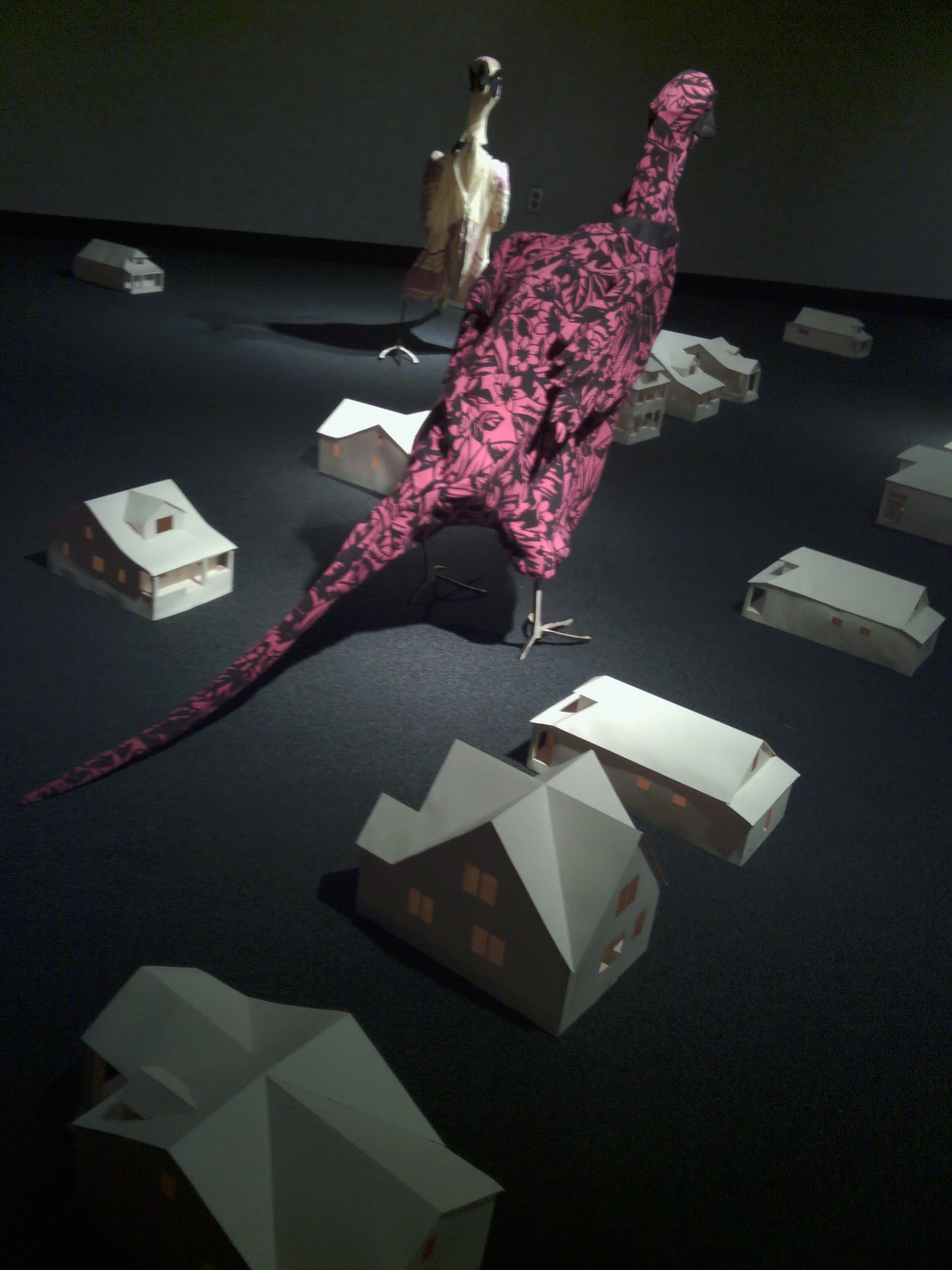

The large piece at the center of the show is a self-portrait of sorts. Three legs of “my” body are anchored by sarcophagi, or miniature versions of houses that I have built or renovated. Each house holds raw cotton. The fourth leg, a Maypole, is made of silk, a material comparatively less toxic in its production. Though contaminated by the problematic history of American indigo, the baby sheep rises as a moment of hope for the next generation.

“Whether Ewe Like It or Not” reckons with my connection and complicity in transnational capitalist systems, bearing witness to an ongoing personal and countrywide miscarriage of justice.